My paternal grandfather died when I was young, well before I could retain any meaningful memories of him. In the fleeting moments I think of him, I visualize the middle-aged man peppered with grey hair and known for his bright, dimpled smile. These are the memories I have of him, thanks to the photos and videos stashed throughout our house. From my father’s anecdotes, Genyuan was an accomplished and well-respected physician, scientist, humanitarian, father, and husband. For most of my life, I didn’t extract any meaning beyond the surface-level knowledge that my grandfather was the ultimate altruist.

Recently, I had the opportunity every sci-fi nerd dreams of: seeing history in real life. I was the first person in my family to peer into the life of my grandfather and grandmother at the dawn of their legacy—before their accomplishments, marriage, children, and grandchildren.

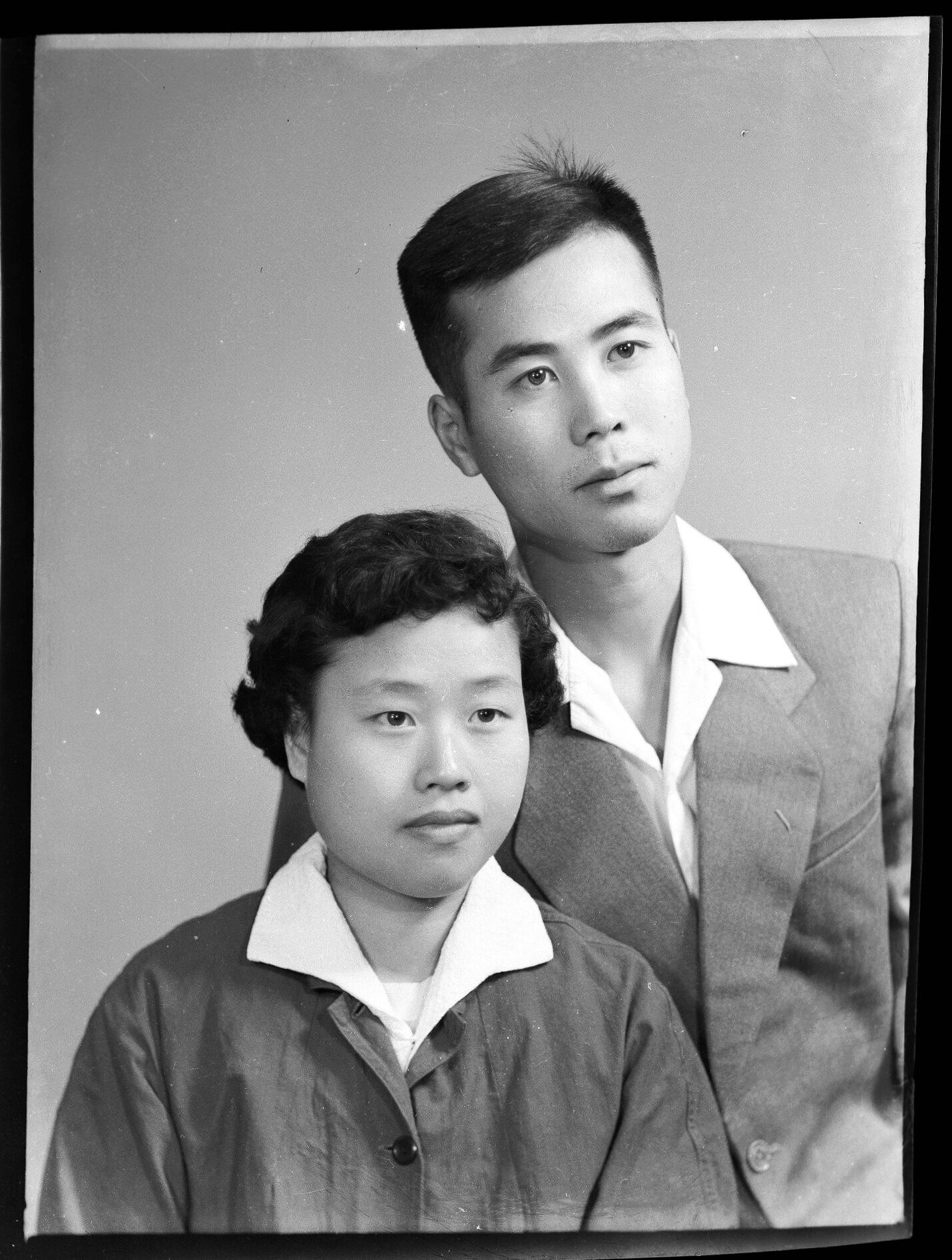

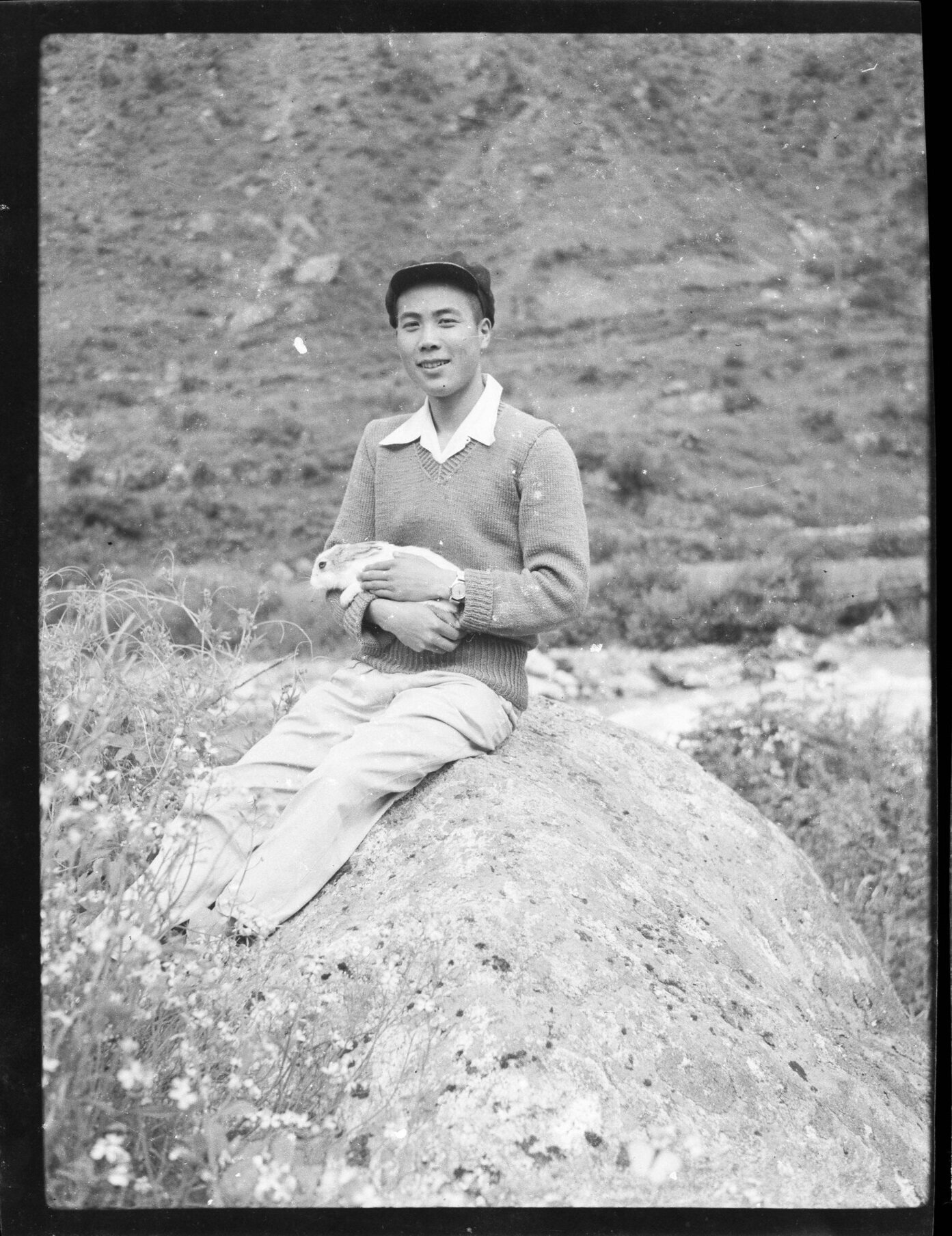

Genyuan Liu, circa 1955.

Tucked away in an unassuming, nondescript box in my basement lay some old passports and other vintage travel paraphernalia. Among them were a few leather 6x6 film negatives holders. In an age where digital reigns supreme, I immediately knew that I had struck analog gold.

It was in that instant that I recalled my father’s early photography lessons to me. Not only was it a lesson to me, but it was also a lesson to him passed on from his father. My grandfather instilled a deep appreciation for photography and the documentation of one’s life through the medium.

Had I not uncovered these photographs of my grandparents in their twenties—the same age at which I am now writing this—I would have nothing to ground their stories. Having these photos to look at gives me invaluable insight into the context of my grandparents’ lives. I could see their lives through their eyes. More importantly, the photos painted a picture that went beyond the perfect, ultimate-altruist portrait my dad had painted of him.

The beauty of photography, specifically film photography, is the ability to curate one’s own life story. In stark contrast to our endless iPhone camera rolls destined to never see another soul, each of the recovered photographs was taken intentionally and judiciously. It served a purpose; it was life captured in an instant. Whether or not posterity ever crossed my grandfather’s mind, the photos he saved enlightened, inspired, and continued his legacy.

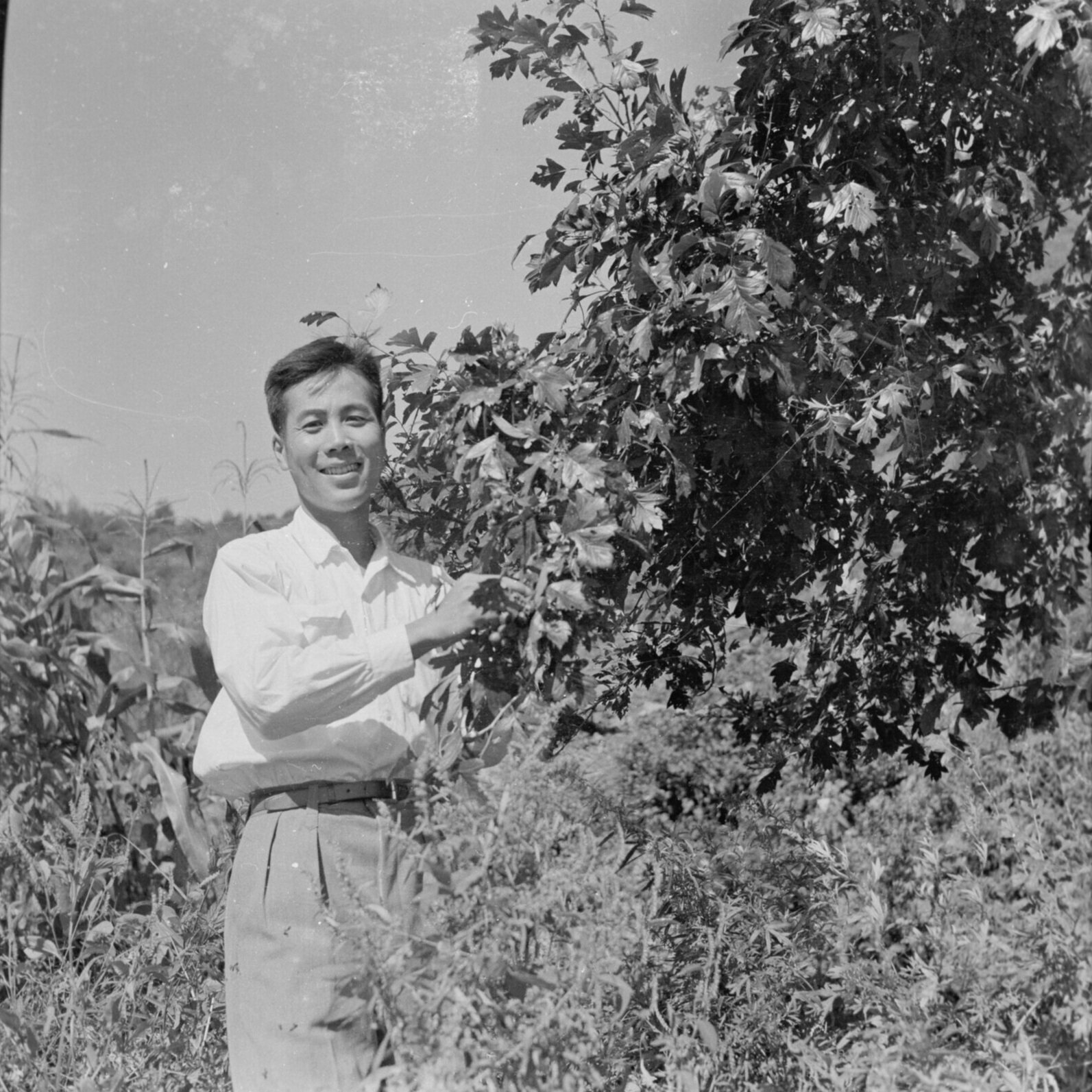

Here is a brief peek into my grandfather’s life as a young man, as curated by him through the photographs he has taken, kept, and passed down.

Images were taken on Zeiss Ikon Super Ikonta III, Zeiss TLR (exact model unknown), and other medium format film cameras. Scanned on Epson v600.

Work in Tibet

In 1953, Genyuan Liu was twenty years old and a new graduate of medical school at Sun Yat-sen University. Around this time, he married my grandmother, Lifeng Mo, in the Great Hall of the People. Shortly after, he was called by his country to join a Tibetan Health Task Force. After four months of walking, riding horses, and climbing snow-capped mountains, the medical team entered the southern tip of Tibet in rural Yadong.

In the spring of 1954, he founded Yadong’s medical center.

In 1957, he built the first medical clinic in the high altitude city of Pali.

In 1959, he built the first rural medical station and trained a large amount of Tibetan medical workers.

In 1961 he was sent to Tibet People’s Hospital in Lhasa and served as director of internal medicine, associate professor, deputy chief physician, and deputy dean of Tibet Medical College.

Between 1961 and 1964, his three sons were born.

In 1973, he participated in the national recruitment as the chief examiner in Tibet and selected the first batch of Tibetan pilots.

In 1981, he was the chief medical doctor in charge of providing care to the President of China who became very ill while visiting Tibet. The President recovered well from his expert care.

Genyuan Liu accumulated rich experience in altitude medicine. In his time, he had the highest cure rate of altitude sickness in the world, and his extensive research in altitude sickness has contributed to our clinical understanding of the condition.

During his 31 years in Tibet, he treated thousands of patients, was fluent in the Tibetan language, and made great contributions to medicine in Tibet - eliminating ethnic barriers, and strengthening ethnic unity. His footsteps can be traced all over Tibet.

After Tibet

In 1984, he served as Vice President of Guangzhou Hospital.

In 1987, he was also the director of the Research Institute of Guangzhou Medical College.

In 1988, he was promoted to chief physician and hired as a member of the Guangdong Medical Malpractice Appraisal Committee.

Genyuan Liu and Lifeng Mo in front of Potala Palace in the 1950s

Genyuan Liu in front of Potala Palace in the 1980s